Negative Yield New York

On Friday, I published my New York Times debut: a guest essay on the excruciating D.C debate over how to “pay for” desperately needed infrastructure and climate packages. Instead of haggling over federal taxes, I argue that Congress should instead tell the Federal Reserve to backstop the municipal bond market for green projects. This would allow the states and cities that want to do the necessary spending for a green transition and climate change mitigation to finance their efforts at interest rates close to those paid by the federal government, which are negative when adjusted for inflation. You can read the piece in print today.

So how, in my personal longue duree, did I end up writing for the Times about public finance and capital markets?

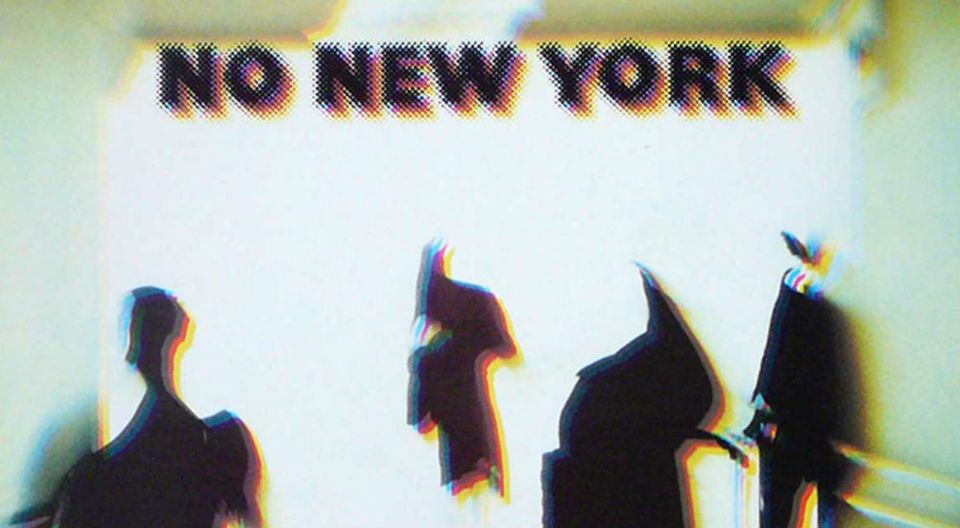

You can probably credit Sonic Youth for my interest in central banking. It won’t shock you to learn that I first got obsessed with cities, their place in the world, and their relationship to money as a direct result of an adolescent fascination with New York’s 1970s and 1980s downtown music scene. Why exactly did that particular demimonde arise? Is it gone for good? Is there a way to create a world where people don’t have to worry about rent and can make whatever ear splitting racket they want?

To answer those questions, I had to understand the 1970s fiscal crisis, real estate, finance — urban political economy, in other words. Rents were cheap in Lower Manhattan because of some deep economic changes: the industries that had built the city’s immigrant working and middle classes had left, the port was in long-term decline, the federal government encouraged suburbanization, and from 1920 through 1965, immigration dried up. And in 1975 when the city had its fiscal crisis, the federal government and central bank decided to make an example of big-spending liberals for purely political reasons. New York was then put at the mercy of private finance, which demanded brutal cuts to services that often lacked any real fiscal purpose but were thought to be symbolically important, like abolishing free tuition at CUNY. The bond market would see these cuts as a sign that New York really was serious about turning the page from its mid-century flirtation with municipal social democracy.

In the short run, the budget cuts necessitated by bond market discipline led to the urban crises of the late 1970s and 1980s, giving the city an overwhelming sense of disorder. The unmanageability of New York scared away even more businesses and residents, which depressed rents further. In this context there was an opening for an avant garde to coalesce, to flout social and aesthetic norms. The city’s postindustrial dysfunction fostered an artistic supernova.

But in the long term, as financialization and globalization took off, New York became the premier “global city,” and its real estate values soared. The story always feels tragic to me. The city pulled itself back from the edge of oblivion. Pre-COVID, New York was richer than it had ever been. Even amidst COVID and after some modest expansions of the local welfare state by de Blasio, bonds for local infrastructure were massively oversubscribed. Yet even though the bond market no longer threatens New York, the economic model created to stay ahead of financial market discipline routinely strangles what makes living here so thrilling.

And however cool it may be to immerse myself in borrowed nostalgia for the unremembered eighties, the city that gave rise to the downtown avant garde was a pretty terrifying place to live for most of its residents. Most of them weren’t hanging out at White Columns. And as the scene was displaced from lower Manhattan to Brooklyn, its most lasting mark on the city seemed to be the gentrification that followed in its wake.

Does it have to be this way? Can avant gardes flourish only amidst social and economic crisis? Must a thriving economy always drive rents to extortionate heights, forcing people to join the careerist rat race if they want to stay in their homes, abandoning their creative impulses?

Liquid Liquid

Recessions devastate local public budgets and lead to brutal cuts to the kind of basic services that keep the social fabric from fraying. States can’t avoid immediate cost-cutting whenever revenues shrink, thanks to local balanced-budget amendments and restrictions on borrowing that could make up for temporary shortfalls. The inability of localities to keep spending through recessions make those recessions worse. The number of public employees also fell by 1.5 million from February to May 2020, and as of June 2021 it remained a million down from its pre-pandemic peak. That accounts for approximately one out of seven outstanding Covid-related job losses.

The federal government is different. Whenever the U.S. government spends without taxing back an equal amount, it issues U.S. Treasury bonds. Investors throughout the world have a near-insatiable demand for safe financial assets. U.S. Treasury bonds are the safest assets of all, because the federal government has a dollar printer. Treasuries currently have a negative yield when adjusted for inflation (even for the notes and bonds that mature after 5, 7, 10, 20 or 30 years). This, in effect, means that these safe instruments — backed by the Federal Reserve and the Treasury — are so attractive that the private sector is willing to pay the government more than it expects to get back after inflation will pay the government to hold its bonds in exchange for a modest-but-better-than-cash return.

Persistent negative real rates on government debt provide a mind-boggling opportunity for public investment. The political economist Mark Blyth and hedge fund manager Eric Lonergan wrote in a 2020 book that negative real rates are a potential source of wealth comparable to “discovering oil.”

The idea turns on its head the neoliberal triumph of independent central banks and financial markets over free-spending public entities like states and cities. Markets were supposed to rein in government spending. Now they are practically shouting for governments to spill red ink.

Yet states and cities, who do most actual day-to-day governing in this country, do not benefit from the enormous piles of investment money, desperately looking for assets that deliver some kind of return or protection from risk.

Currently, local public debt is very illiquid compared to mortgages, Treasuries or corporate debt: that is, they are rarely resold by their original purchaser. Municipal bonds rarely trade on the secondary market and are usually held by local retail investors for tax breaks. Treasury bonds, however, are one of the most liquid assets in the world. They are bought and sold countless times every day. Investors like to buy treasury bonds because they know that they can always sell them if they need cash quickly. With state and local bonds, it’s the opposite.

That makes it very difficult for borrowers aside from a few big, sophisticated jurisdictions like California or New York that frequently issue bonds to know if there’s a demand for their debt at all, nevermind on what terms. States and localities unsure if they’ll be able to find investors to buy their debt often neglect public investment in the first place. But interventions like the post-2008 Basel III bank capitalization requirements, which classified municipal debt as the kind of high grade collateral big banks have to hold in case of emergency, can produce reliable secondary market investor demand that drives down yields. The proposals I wrote about in the Times essay would all create a secondary market to buy and resell government debt, turning an illiquid market into a liquid one.

We have a real world example of how successful this could be. The European Central Bank’s pandemic backstop for EU member nation debt was so successful that this past year, Portugal and Greece, a small and highly indebted countries with GDPs a fraction of the size of New York City’s, managed to join the “negative rates club” (as the Wall Street Journal put it) alongside Germany and France — meaning that interest was negative in nominal terms, not just after adjusting for inflation. Investors paid those former “basket case” governments to hold their money.

If Portugal and Greece can have a negative yield, why can’t New York City?

Negative Yield New York

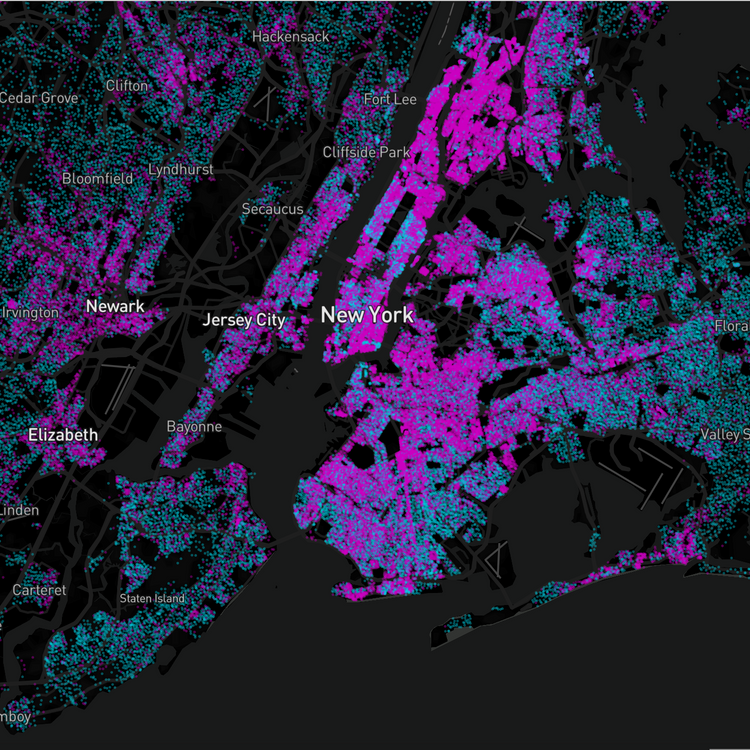

So underlying all my interest in political economy, public spending and finance is the dream of Negative Yield New York. If the city were able to borrow at rates close to those enjoyed by the federal government — that is, lower than inflation — what kind of city might we build?

I wrote about the need to make enormous investments in climate mitigation and greening the city’s infrastructure. But once the city gets access to extremely low-interest credit, it could also invest in massive amounts of new housing to drive down the cost of living as well as cultural infrastructure: the city could create new studios, rehearsal spaces, galleries, and performance venues to ensure that its vital artistic economy can thrive alongside other sectors that have increasingly crowded out the underground.

So that’s my secret. While I talk a good game about “necessary investments” and the climate crisis, what I really care about are bands. Hopefully some Federal Reserve officials and members of Congress turn the proposals discussed in my Times essay into reality, so that when my pre-pandemic band can get back together, we’ll have an easier time booking our practice space.