NYC Still Got It: Post-Primary Edition

Pictured above: our potential new Mayor discusses his favorite New York City pasttime

Here we are on the other side of two epochal moments in New York City’s political history. First, and most importantly, I published my first newsletter essay on class, housing, and the NYC Democratic primary. The response was far better than I could have expected. I owe an enormous thanks to all who read and shared the piece as well as subscribed. The reaction on social media and uptick in subscriptions made my month.

Second, the mayoral primary actually took place.

Now the real work begins: reconciling pre-election takes with initial first-choice results. My thesis held up in some important ways and needs clarification in others, which I will address in two posts.

The first will look at what I got right about how “gentrifiers” old and new voted. Here, I believe my post was totally correct.

The second will look at what Eric Adams’s first place finish means for the city’s politics, along with divisions between market rate and stabilized renters. I admit I may have gotten a bit over my skis in my treatment of Adams and his base, but my critics also overextended themselves. His first place finish does not at all herald the triumphant return to a pre-woke, pre-defund Democratic party political culture, nor does his success with many lower-income black and latino renters necessarily imply that the nature of one’s housing tenure does not profoundly shape political behavior. Rather, the first round results represent a successful defense by the aging establishment against a fractured field, but only that. Going by first round percentages, Adams’ victory would be the weakest successful Democratic mayoral primary performance since Ed Koch won by a hair in 1977.

Now that new shit has come to light, here is how I would revise my thesis: “the contemporary left is a movement driven by young people who rent their homes at market rates, a class that is swelling in number. However, people who own property or live in older rental units insulated from market forces still dominate our politics.”

What I got right

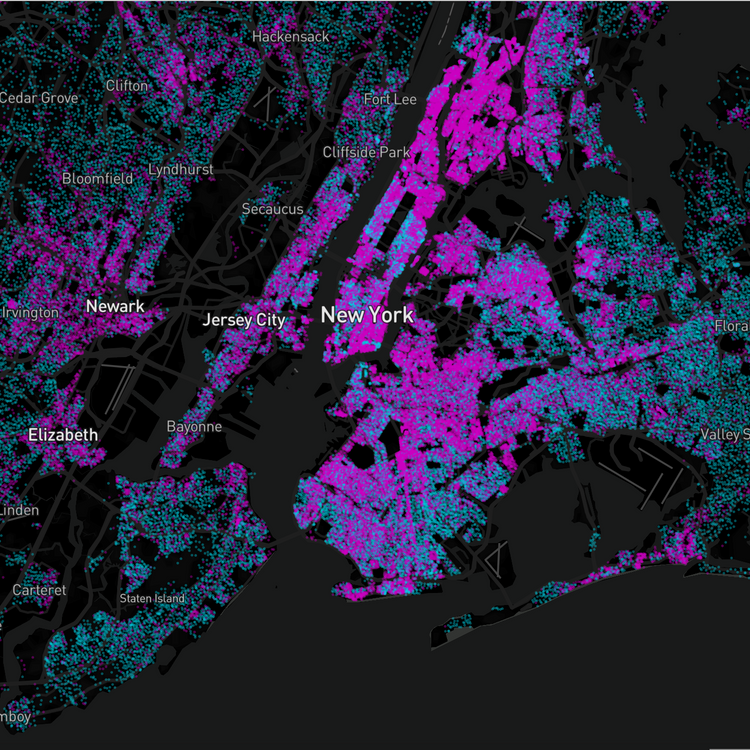

Let’s begin by looking at the New York Times’ detailed map of first-round results.

What this says about the New York City left

As a diagnosis of the new left’s growing but still constrained power, the essay was vindicated. Wiley was a weak candidate with little credibility in local politics who lingered in mid-single digits in most of the campaign’s polling. But she surged to second place when her progressive rivals collapsed, important new left figures like AOC finally endorsed, and voters overwhelmingly concentrated on the gentrification frontier coalesced behind her. Wiley’s strong showing almost exclusively in the later-gentrifying neighborhoods of Brooklyn and Western Queens, where left-wing activists have racked up three years of surprise victories against establishment-backed incumbents, was sufficient to catapult her to the top tier of candidates. She beat rivals who had far more experience in local elections, got more media coverage, or had closer ties to deep-pocketed donors. She has an outside chance of being the next mayor in our new ranked-choice voting reality. But it is very much an outside chance.

Going by the cross-tabs of Data For Progress’ final poll, Wiley put together exactly the kind of new left coalition I described in my original post. She dominated with younger voters. Her support was almost perfectly split between black, white and hispanic voters.

I’ve heard it said that Wiley’s base and the New York City left, to the degree that they are the same, are just college educated elites, and the new left’s ideology will never have a mass base. Indeed, she got more support from college graduates than either Garcia or Adams. But this misses important generational context. Yes, Wiley did disproportionately well with college educated voters relative to non-college voters, who favored Adams by a wide margin. But from 1968 to 2018, the share of Americans aged 25 to 37 — those newly entering the workforce and political life — with only a high school education or less shrank from 73 percent to 33 percent. The share of Americans in that age range with some college, a bachelor's degree, or higher levels of education rose from 28 percent to 67 percent. That’s more than twice as many people in the millennial generation who have at least some college education than those without.

A college education no longer necessarily makes one an elite, totally out of touch with the masses — it in fact is the basis for shared experience across a generation. So is the resultant debt, and the fact that getting on the meritocratic treadmill no longer guarantees decent healthcare, retirement savings, or quality housing near good job prospects.

Contrary to the assertions of many national pundits who pronounced the death of New York City’s left in the wake of Eric Adams’ first place showing in the mayoral primary, there is indeed a wide and growing class receptive to the kind of millennial progressive politics Wiley tried to embody. This class just isn’t the biggest one in the electorate, nor does it turn out at the same rates as older more established parts of the Democratic coalition. Yet.

Better, more credible left-wing candidates who could form city-wide coalitions had a banner election day. Brad Lander, the pro-defund city council member and longtime local protest fixture, trounced the far more powerful and connected former City Council Speaker Corey Johnson in the comptroller’s race because he was able to get both the young left and the older, wealthier liberals. Likewise, Jumaane Williams has close ties to more established black political networks in central Brooklyn and the Black Lives Matter/Defund movement. He managed to more than double his victory margin from his first city-wide campaign in the 2019 open special election for public advocate to the 2021 democratic primary for the same office, from 32.8 percent two years ago (fourteen points better than the second place finisher) to 70.8 percent last week (almost fifty points better than the second place candidate). The young lefty Antonio Reynoso appears to be winning the Brooklyn borough president race over politicians from older black and white neighborhoods in the borough’s southern and eastern fringes, who are closer to the local Democratic party establishment. Just as importantly, the most right-wing candidate for Manhattan DA who attempted to capitalize on a supposed massive backlash against defund lost her race to a progressive prosecutor. And upstate in Buffalo, avowed socialist India Walton beat a four-term incumbent mayor in a city that is older, blacker, and more working class than New York City, with a mere handful of the kinds of college educated radicals associated with the metropolis' socialist scene.

Though DSA only appears to have won a few of its six council races, it came in second place in all but one contest. Additionally, the idea that the millennial left is somehow a spent force is complicated by the fact that the first place candidates who beat DSA’s champions were typically very young left wing politicians themselves, just not self-described socialists. Brooklyn’s 35th council district saw one of the most contentious races featuring a DSA-endorsed candidate. The non-DSA, establishment-backed first place finisher Crystal Hudson proudly embraced defunding the police, decriminalizing sex work, and treating drug addiction as a public health problem rather than a criminal justice one. The next city council will still be the most left wing in New York’s living memory. Left wing politics pitched at young voters can and do win elections by healthy margins in districts with lots of those young voters. And those young voters are going to keep growing as a share of the city’s electorate, faster than rich white liberals or nonwhite outer borough party stalwarts.

The left’s prospects will get easier as the city reopens, because crime will fall, thanks to a variety of changes to daily life that have nothing to do with policing. People will use public spaces more heavily and put more “eyes on the street.” Working class jobs will return. Socially grounding institutions like schools will be able to reconnect with youth. In-person social service providers can more easily reach those most marginalized people who fell through the cracks during the most traumatic and disruptive year in New York City’s history. Household stress will alleviate leading to less domestic violence (a major but under-discussed contributor to this year’s spike in interpersonal violence). When crime falls — and I am willing to bet money that it will — Eric Adams’ tough-on-crime message will have much less salience.

We saw exactly this pattern during the late Bloomberg years, and it was responsible for de Blasio’s election. As crime fell to absurdly low levels during the 2000s, it was harder and harder to justify the NYPD’s abusive, unchecked reign over the city. Older black and latino voters who may have thought of themselves as partners with police during the bad old days, and who likely voted for tough-on-crime Adams in 2021, could see in Dante de Blasio their own children or grandchildren, who had stories of humiliating, pointless police stops. Everyone but the billionaires began to realize that the main threat to their ability to live and thrive in New York City was not crime, but cost of living. The cops weren’t keeping New Yorkers safe — they were keeping New York safe from New Yorkers, for the global capitalist class. The same thing will happen again.

Taken in sum, the results of the primary suggest that the young left should ignore the pundits who claim last week’s primary results mark “peak woke” and the electorate’s comprehensive rejection of their politics. We are nowhere near peak woke. We have barely begun to see woke politics.

What this says about the generational divide between “true gentrifiers” and more recent arrivals

And similarly, I was correct that there is a divide between the younger multiracial voters in the gentrification belt who backed Wiley and the older liberal whites of Manhattan and Brooklyn’s wealthiest neighborhoods, who broke for Garcia.

Now, I have not been shy about my enthusiasm for Garcia. When I squint hard enough, I can turn her into a sewer socialist. But that is plainly not the campaign she ran. Garcia stressed managerial competence and improving core city services without any social justice baggage. She opposed raising taxes on the wealthy. She told a Vanity Fair reporter she would get to work early, and that she would prioritize “setting up metrics and paying attention to them and ensuring that you are funding the things that you think are most important.” As she playing into the Bloombergian manager mythos, she also implicitly contrasted herself with de Blasio, who irked wealthy whites by showing up late to everything, refusing to give up his drive to the Park Slope YMCA, and generally seeming checked out. This paid off when she got the New York Times’ endorsement, the ultimate mark of Manhattan establishment approval.

Garcia's one-time boss Bloomberg was quite clear that he managed the city so effectively because he wanted to transform it into “a high-end product, maybe even a luxury product,” and people capable of affording a luxury product demanded the best from their government. Garcia got almost all her votes in neighborhoods that profited the most from Bloomberg’s twelve-year effort to make the city as inviting as possible to rich people: Manhattan below 96th street (but not the East Village and Lower East Side, where some young and non-white people still manage to hang on), Park Slope, Carroll Gardens, and the most comprehensively redeveloped portions of the Williamsburg and Long Island City waterfronts.

The people who live in these neighborhoods not only enjoyed astronomical gains on the value of their real estate, they also have the late career professional incomes to keep up with rising tax bills. Ever since the business class and wealthy professionals took control of the city’s political economy in the wake of the 1975 fiscal crisis, all improvements to city services have been justified as means of making the city more “competitive” in terms of attracting big employers, investors, ultra-rich households, and the most elite professional talent from around the world.

As this high-end demand soared under Bloomberg's watch, he also downzoned huge swathes of the city, more than he up-zoned. A local political economy that draws in tons of purchasing power without simultaneously increasing housing capacity necessarily produces a white-hot housing market. That sucks for the lower-income longtime residents and the newest arrivals outside the absolute top tier of the global elite. But it’s great for incumbent property owners who got here before the real estate rush reached its apex and were themselves on the professional fast track. When Garcia sold herself as the most Bloombergian candidate, the people who had benefited most from her former boss’ version of sewer socialism for the rich pricked up their ears.

The irony, of course, is that no one talked about her low-key radical plan to upzone low-density housing not just in one or two ultra-rich neighborhoods, but throughout the city. Nothing drives down home prices more than a glut of homes that exceeds supply. Garcia probably would be the best candidate to make the city most inviting to the business class, but that doesn’t mean she would protect local homeowners’ property values by restricting housing supply in the same way that Bloomberg did.

Some simulations suggest that Garcia is more likely than Wiley to upset Adams in RCV. It’s hard to fathom how weird the city’s politics would become in such a situation. A previously low-profile Bloombergian mayor will have to manage a city split between her own wealthy and powerful but shrinking, aging base; a growing and ever-more radical left packed into a few neighborhoods leading to volatile political outcomes and fueling unpredictable social movements; and an experienced nonwhite political establishment deeply rooted in the outer boroughs that feels their victory in Adams has been snatched out of their hands. She'll have to do it without any political operation of her own, nevermind billions of dollars in personal "philanthropic" slush fund money to pay off every power broker in the city.

For all Garcia’s talk of managerial competence, nothing in her background suggests she can necessarily manage politics, which could be quite tense. But her actual policy program actually provides a pretty good set of tools for lowering the city’s political temperature: go all-in on green public works and thus provide tons of jobs for organized labor. Improve central city services and make streets more inviting to commuters and tourists, and thus appease the Manhattan and corporate elites who have benefited from the city’s global status. Institute a youth jobs guarantee which will reduce crime — which would quietly obviating the “need” to overpolice idle young nonwhite men. And finally, build a shitload of new housing everywhere to give everyone relief from the increasing rent burden. It won't hurt either that legal weed stores will come online during the next mayor's term.