Renters, Owners, and the New York City Left's Mayoral Ennui

So it’s come to this: there’s a week to go before the New York City Democratic mayoral primary. Eric Adams, a nakedly pro-machine former Republican and cop, leads most polls to run the city that more than any other has birthed America’s contemporary left. What gives? Why has New York’s new left been such an underwhelming force in 2021, after a rollicking three year stretch that began with AOC’s surprise 2018 victory that arguably reshaped America's political trajectory?

A lot of the media discussion has focused on the left’s rhetoric and candidates. What I’d like to argue here is that there is a deeper structural explanation for the New York City left’s troubles in 2021. The source of the New York City left’s strength in legislative races from 2018 to the present as well as its weakness in the current mayoral race are one and the same: Fundamentally, the contemporary left is a movement driven by people who rent their homes, a class that is swelling in number. However, people who own property still dominate our politics. The relationship to asset ownership, more than race, ethnicity, feelings toward police, union affiliation or any other social category, explains the rapid development of the New York City left and its current limitations.

New York has been a hotbed of left-wing political organizing because it is home to a growing and diverse population of renters, the largest in the country, and renting sucks. It’s alienating just like Marx said wage labor is alienating: you know you’re getting screwed when you pay your rent, that someone is growing their wealth by eroding yours. In fact, the better the city’s economy does, the more precarious life feels: Property values rise faster than incomes and drive up rents, increasing the risk of losing one’s home to someone willing to pay that higher price. Though the housing crisis has been brewing for decades, since 2008 it has increasingly hit even highly-educated workers, shrinking the college earnings premium and driving people with social and cultural capital further to the left.

The rent burden now links a whole generation across social lines. This is a national phenomenon, but it’s most pronounced in New York City. Establishment Democrats have not tapped this deep well of shared grievance, creating an opportunity for a generation of political insurgents. But organizing and mobilizing renters is enormously difficult, while property owners are at the heart of America’s political economy and see their power grow along with their home values.

Here I am drawing on research by political scientists Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper, and Martijn Konings of the University of Sydney. As they argued in a 2019 paper that was turned into a book the following year, asset ownership, in particular residential property, is the primary shaper of class relations in the 21st century, rather than the nature of one’s work. Homeowners share a common interest in increasing the value of their property, regardless of what they do for a living, or how educated they are, or their racial or ethnic background. As homeowners increase the value of their homes relative to wages, they raise the barriers to property ownership and shut out a wide range of young people — again, regardless of their occupation, education, or racial or ethnic background. This dynamic is the heart of the stark generational political divide found throughout the Anglosphere. As the trio wrote, “In the present era, where mid-size homes in large Western cities often appreciate by far more in a given year than it is possible for middle-class wage earners to save from wages, such a continued focus on employment as the main determinant of class is increasingly untenable.”

What increases property values? Demand that exceeds supply. Demand for urban property exploded from the 1970s to the present thanks to an macroeconomic transformation referred to as "the neoliberal turn," which unshackled capital from national borders and political constraints. As sociologist Saskia Sassen explained in her seminal work The Global City, multinational firms and investors dominate capitalism in the late 20th century and early 21st century, managing a mind boggling array of deals, operations and risks across borders. These firms and investors can only conduct their business with expert help from many different elite professionals, who agglomerate in places like New York City. Those elite professionals in turn demand a suite of lower-paid human services to feed themselves and maintain their households. Marx wrote that 19th century industrial capitalism created “whole populations conjured out of the ground.” So the globalization of capital in the neoliberal era has conjured its own populations in gentrifying former industrial and waterfront districts around the world, the elephants’ graveyards of Marx’s capitalism.

If in Marx’s time it was your boss who alienated the surplus value of your labor, today it is increasingly your landlord, be it a faceless LLC owned by an institutional investor or a seventy year old West Indian immigrant with a city pension. Owners have a strong incentive to increase the value of their assets while holding down costs, just like capitalists have a strong incentive to increase the productivity of labor without raising wages.

Considering how much political decisions can affect home values, it’s no surprise that homeowners are very politically active. According to a 2019 paper analyzing voting behavior by 18 million households, buying a home was associated with significantly higher turnout. Homeowner turnout doubled for zoning ballot initiatives, which directly affect home values. What’s more, the effect grew more pronounced for owners of more valuable homes. As the authors wrote, “homeowners have special influence in American politics in part because their ownership motivates them to pay attention and to participate.” And homeowners have a pretty simple ask of politicians: maintain the status quo. Politicians don’t have to do much to reward their constituents with higher home values at a time of increased housing demand.

Renters, however, have a lot to lose if things stay as they are. The market generally doesn’t produce an adequate supply of affordable rental housing since the two big costs, real estate and materials, stay the same for “affordable” and “luxury” construction in a given location, so affordable units just offer developers lower margins. Affordable housing only gets built at scale in response to government action or a massive increase in renters’ purchasing power. Without some deliberate effort to create new housing or give renters a lot more money, a growing number of renters have to compete for a shrinking supply of homes, and prices surge.

Given their poor prospects in the current housing market, it’s unsurprising that renters are significantly more left-wing than owners: they supported Bernie Sanders over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 Democratic presidential primary, and favor increased government spending typically financed through taxes on high incomes and property. But both federal housing aid, social welfare, and workers’ incomes have atrophied for decades, and local politicians don’t have the tools to reverse those trends. So with little to gain from political outcomes, renters vote less often.

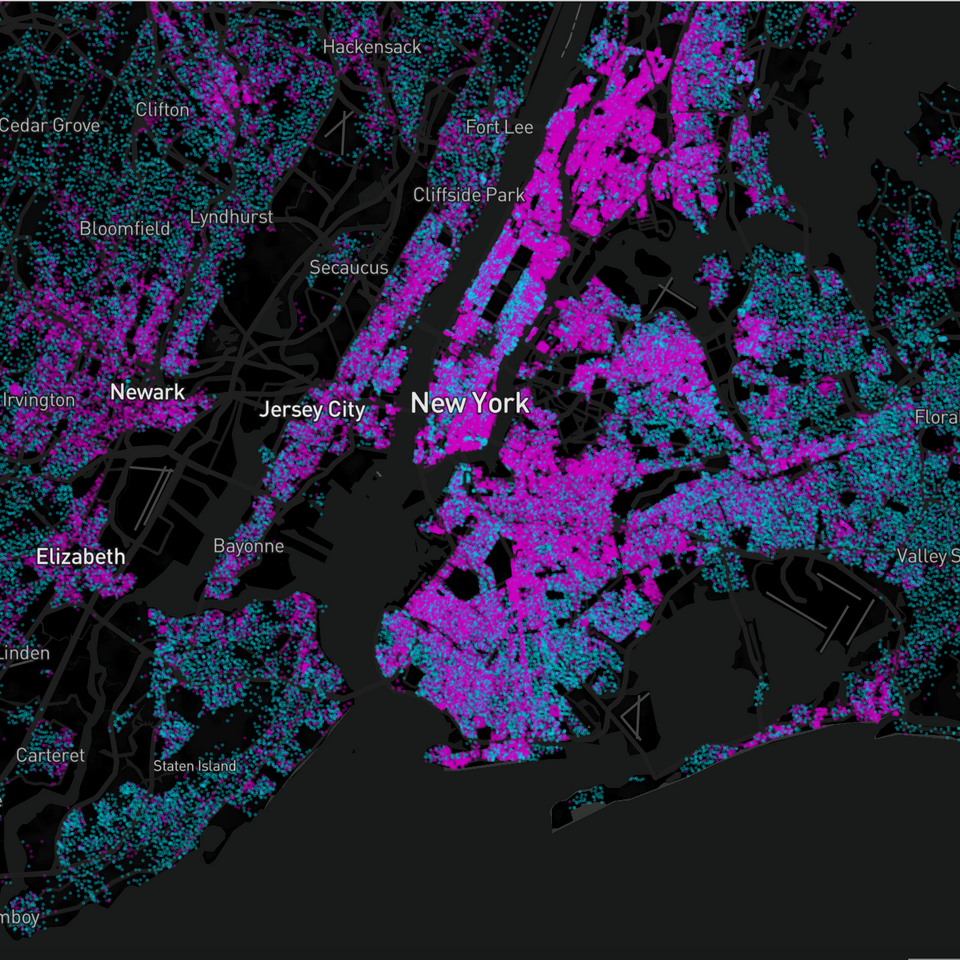

Let’s turn to New York. Here’s a map of census data showing every renter and owner in the city, pulled from a website created by Ryan McCullough of Mapbox. Renters are pink and homeowners are blue.

The typical story of class struggle in America pits the industrial bosses and international capitalists against the industrial workers and those dispossessed by the creative destruction of modernity. However, this narrative is complicated by home ownership. Yes, the neoliberal turn decimated industrial employment, labor unions, and government jobs in the decades after the 1970s. It got worse to be a worker over that period. Employment opportunities increasingly accrued to those with elite educations or those who would work for low wages. But many members of the old American urban working class bought homes in desirable cities, thanks to decent pay won by their once-powerful unions and a raft of state and federal policies that encouraged the development of middle-class owner-occupied homes. After immigration laws were loosened up in the mid-1960s, people from around the world moved to post-industrial cities where they worked at all levels of the new international service economy. The job opportunities available to immigrants were poorer than the union manufacturing jobs of old, but it was easy to start businesses and housing was relatively cheap. So some of the new immigrants also bought property.

Taken together, this multiracial class who disproportionately own their own homes populate the whole outer arc of New York City: from the Northeast Bronx to Eastern Queens to Southern Brooklyn and on to Staten Island. Though many of these people are what you would call working class going by job or income, they may also be quite asset-rich thanks to skyrocketing home values. These New Yorkers are Eric Adams’ political base. Considering they have more to gain from rising home prices than rising wages, it is no surprise they are backing the candidate most aligned with the city’s real estate industry, who share their common interest.

Today, the latest arrivals to the beating heart of global capital find that the real estate has already been split between corporations, big landlords and the super-rich in Manhattan, and older homeowners elsewhere. Young people without a chunk of inherited wealth for a down payment have little choice but to rent, whether they are a recent immigrant working in a restaurant or a recent college graduate working as a junior equities analyst. Renters concentrate in the purple center of the map, where apartments were built for industrial workers a century ago, some newer “luxury” rental towers go up today, and rowhouses get split into multiple units. Even though the most elite of these new workers make much higher salaries than the older working classes that preceded them, the housing market is so tight that the PMC’s money doesn’t go as far, at least when it comes to acquiring homes. Some may be cash-rich but they are asset-poor compared to members of earlier generations at the same point in their lives.

And really, most of them aren’t cash rich. Chances are they moved to the city not to get a plum gig in finance, an industry that doesn't actually employ many people, but to have any shot at a job at all, as much of the rest of America has hollowed out. Their paycheck is increasingly eaten away by student debt and insurance premiums. Relatively few are unionized so they can’t count on raises or employment protections, but they can count on the rent going up as more of their kind arrive and compete for scarce housing.

From 2006 to 2016, renters increased as a share of New Yorkers while owners decreased, a pattern that was repeated in 97 out of 100 of the country’s largest cities. As the above map shows, renters disproportionately pack into the few centrally located, transit-connected parts of the city that are somewhat more affordable than the luxury districts of Manhattan and Brooklyn: North and Central Brooklyn, Western Queens, the Lower East Side, Upper Manhattan, and the South Bronx.

The better educated among these renters are often tarred as gentrifiers, but that’s not quite right. As originally defined by British sociologist Ruth Glass in the 1960s, gentrification refers to a process whereby professionals purchase and “improve” cheap older working class housing in central cities, typically reducing the number of units available by reverting split-up rowhouses back to single family homes. Renters can’t afford to do this anymore.

New York City’s true gentrifiers arrived decades ago, settling in the original “transitional” neighborhoods of the Upper West Side, Tribeca, SoHo, Chelsea, the West Village, Brooklyn Heights, Carroll Gardens, and Park Slope. These are the original yuppies, people for whom a college education was a golden ticket into the professional elite rather than the bare minimum to enter the white collar workforce. They resemble more recent arrivals in their educational and professional profile, but because they got to the city before real estate values surged faster than incomes, they were able to buy their own homes. They are socially liberal, but loathe to support policies that threaten the value of their real estate. That makes them fickle allies for the new left.

With the social and economic geography out of the way, let’s turn to politics. Here is a Gothamist map of results of the 2018 gubernatorial primary race between incumbent moderate Andrew Cuomo (purple) and progressive challenger Cynthia Nixon (orange).

Nixon swept the neighborhoods dominated by the original gentrifiers and younger renters. These voters shared liberal social values and a revulsion to Cuomo’s corruption, along with demands for services that improve life for central city residents, if not outer-borough drivers or billionaires. The coalition was woefully inadequate to defeat Cuomo city- or state-wide, nor did it extend to the neighborhoods of upper Manhattan and the Bronx that are home to many low-income renters, but few people with college degrees.

Here’s a Gothamist map of New York’s voter turnout from that primary election. Darker colors indicate higher turnout.

The lightest areas on this map correspond almost perfectly to the pink dots in the map of renters and owners. Ditto for dark areas and the blue dots for owners. Turnout is lower in renter neighborhoods than owner neighborhoods. Aside from Park Slope, the neighborhoods where Nixon did well saw moderate to low turnout. Low turnout in these areas was bad for Nixon — she was swamped by Cuomo’s huge pools of support throughout the city and state — but good for her allies in state legislative races, because they didn’t have to get that many votes to beat incumbents in their smaller districts.

These dynamics explain why the New York City left has a lot of potential to grow but many hurdles in its way. The ranks of renters are growing, but they remain geographically concentrated and hard to turn out, limiting their power in city-wide elections. To break out, the left needs to do two big things.

First, it must build up candidates with appeal beyond those neighborhoods that attract many young renters. At the beginning of the mayoral race, Scott Stringer looked like a good vehicle for this strategy, considering his city-wide political connections and base of support in the wealthy high-turnout neighborhoods of Manhattan and Brooklyn. But considering his long history of changing his ideological position with the political winds, the left did not trust Stringer enough to stick with him through allegations of sexual misconduct, however credible. Dianne Morales attracted more grassroots excitement, but she lacked any plan to grow her base of support beyond youth activists. In any case, her campaign imploded thanks to her own managerial incompetence and poor hiring of inexperienced operatives. Maya Wiley now appears the progressive’s last best hope for 2021, but there is a good reason she failed to catch on for most of the campaign: she is a creation of MSNBC, elite nonprofits and the legal profession, not an actual politician. Based on the number of donations she received, her core base of support is in the same wealthy precincts of Brooklyn and Manhattan where Stringer expected to do best, but she lacked Stringer’s citywide political relationships. Wiley owes her last-minute surge not to anything she has done, but to the other progressives’ collapse and a late endorsement from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the unquestioned champion of a generation of alienated millennials. In future mayoral races, the left needs to consolidate between one candidate with citywide support.

To make that task easier, the left should fully embrace policies that expand the rental belt. Their likeliest supporters are packed into just a few neighborhoods because of zoning decisions made during the Bloomberg administration, which increased market-rate rental density in exactly the neighborhoods where the left now does so well, but froze outlying areas as low-rise, owner-occupied neighborhoods. Following the lead of Minneapolis and Portland, the left should push for a citywide rezoning that eliminates local barriers to dense rental housing. Stringer and Wiley support rezoning some of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the city like SoHo, which is fine, but unlikely to fundamentally change the city’s political geography to the benefit of a tenant-powered left. Only a moderate, Kathryn Garcia, has embraced eliminating exclusionary single family residential zoning citywide. Though she deliberately distances herself from self-identified progressives, her plan to massively increase housing density provides the surest strategic route to the left’s long-term political success.