NYC Still Got It: RCV Not-Quite-Final Results Edition

When New York City’s initial round of primary results rolled in late last month, Eric Adams was quick to declare he had been handed a sweeping mandate by a city-wide coalition of multiracial moderates. The social media-fueled left wing fervor of the past few years had been illusory, he said, because “social media does not pick a candidate...People on Social Security pick a candidate.” Democrats across the country should herald his example of non-white anti-left wing politics as the wave of the future. National media and left-skeptic pundits readily parroted Adams’ interpretation of the topline numbers. Adams “Built a Diverse Coalition That Put Him Ahead in the Mayor’s Race,” read a New York Times headline. In another story, the Times reported that Black and Brown voters “flocked to his candidacy” while leftists struggled to connect with nonwhite voters. The National Review said that Adams was “an anti-Leftist Wake-Up Call.”

Many have pointed out the disconnect between the initial results and the latest ranked choice results that show him barely beating Kathryn Garcia by fewer than 9,000 votes, with almost 140,000 ballots discarded for lack of a ranked top-two finisher (there are still some absentee votes left to count, but not enough to put Garcia over the top). But really, none of the talk about Adams as a sign of things to come made much sense at the time. In fact, Adams had a very weak first place showing compared to his predecessors, and his ranked choice win is also weak compared to past runoff winners.

Adams’ victory does not show that there is a brewing anti-left movement within the Democratic party. Instead, it indicates that one of the party coalition’s largest and most stalwart blocs, aging black and latino voters, aligned with big real estate money and mounted a successful defense against constituencies newly entering the Democratic electorate, but not yet organized or sizable enough to take over the party.

As mayor, Adams will have the opposite of a city-wide mandate: instead, he’ll have the support of his core constituency, real estate donors, cops, and no one else. And that core constituency is shrinking, while the bloc of voters he gleefully antagonizes is growing. A lot of that shift is down to — you guessed it — the nature of the city’s housing market, which I will explain in my next post.

Adams’ historically weak victory

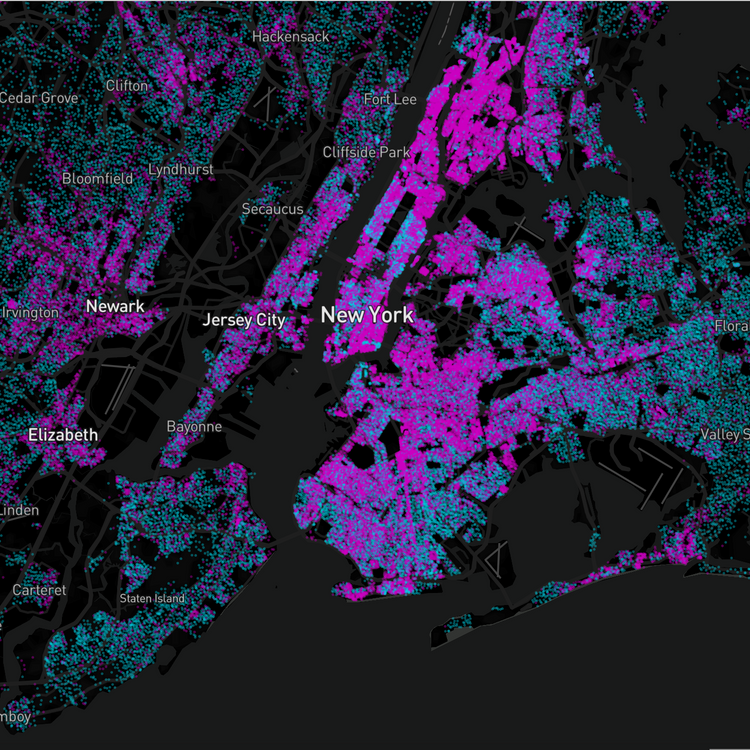

Here’s the New York Times’ summary and map of last week’s first-round results.

And here’s a map of the 2013 Democratic mayoral primary results.

De Blasio’s first place finish was more than eight points higher than Adams’. He had a margin over the second place finisher Bill Thompson almost twice as large as Adams’ margin over Wiley. De Blasio also managed to actually pull together a multiracial, all-city coalition, whereas Adams' coalition was concentrated in Upper Manhattan, the Bronx, and the arc of neighborhoods around Jamaica Bay, with relatively little success elsewhere.

Likewise, Adams did worse than Bill Thompson in 2009 (a crushing 71%), Freddie Ferrer in 2005 and 2001 (39% and 35% respectively, though he lost the 2001 nomination to Mark Green in a runoff), Ruth Messinger in 1997 (40%) and Dinkins in 1989 (51% against the incumbent Koch). Not since 1977, when Ed Koch bested Mario Cuomo with a mere fifth of the vote, has a first-place finisher won a smaller portion of the city’s Democratic primary electorate.

Ranked Choice Voting and runoffs are not strictly comparable — RCV ensures many more voters ultimately have a say in the final outcome. With that caveat out of the way, Adams also did much worse in the final RCV results than past runoff winners did in the final round. Mark Green ultimately won the 2001 runoff against Ferrer by two percent and almost 16,000 votes, or twice Adams’ RCV margin against Garcia. In the 1977 runoff, Koch defeated Cuomo by more than 78,000 votes for an almost ten percent margin.

Now, that’s not to say that if Adams ultimately becomes mayor, he’ll necessarily be a politically weak one. After his 1977 “law and order” campaign, Koch served three terms before the city ultimately soured on his deliberately polarizing style. Adams also campaigned on law and order and outer borough racial resentment, albeit of older blacks against younger whites rather than the other way around as in Koch’s case. Could he succeed with Koch’s electorally successful but socially divisive playbook again in 2021?

I seriously doubt it. Koch was swimming with the neoliberal tide in 1977, but Adams is trying to beat back against the political currents. The bench of capable left wing politicians who can seriously challenge him is only growing. His extensive ties to some of the Democratic machine’s least-savory figures and penchant for bizarre, unappealing public spectacles will not endear him to wealthy whites. His tough on crime messaging will grow less salient if crime falls, as indeed it did in June 2021 relative to the same month a year ago. And most importantly, his political base is shrinking. I will address this last point and what it has to do with the political economy of housing in another post to come this week.